12 KNAPSACK AND GRAPH OPTIMIZATION PROBLEMS

John Qu / 2020-06-13

What are the characters of optimization problem?

In general, an optimization problem has two parts:

What’s the main things to take away from this chapter?

- Many problems of real importance can be formulated in a simple way that leads naturally to a computational solution.

- Reducing a seemingly new problem to an instance of a well-known problem allows one to use preexisting solutions.

- Knapsack problems and graph problems are classes of problems to which other problems can often be reduced.

- Exhaustive enumeration algorithms provide a simple, but often computationally intractable, way to search for optimal solutions.

- A greedy algorithm is often a practical approach to finding a pretty good, but not always optimal, solution to an optimization problem.

12.1 Knapsack4 Problems

Why it is not easy being a burglar?

In addition to the obvious problems (making sure that a home is empty, picking locks, circumventing alarms, dealing with ethical quandaries, etc.), a burglar has to decide what to steal. The problem is that most homes contain more things of value than the average burglar can carry away. What’s a poor burglar to do? He needs to find the set of things that provides the most value without exceeding his carrying capacity. Suppose for example, a burglar who has a knapsack that can hold at most 20 pounds of loot5 breaks into a house and finds the items in Figure 12.1. Clearly, he will not be able to fit it all in his knapsack, so he needs to decide what to take and what to leave behind.

| Value | Weight | Value/Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clock | 175 | 10 | 17.5 |

| Painting | 90 | 9 | 10 |

| Radio | 20 | 4 | 5 |

| Vase | 50 | 2 | 25 |

| Book | 10 | 1 | 10 |

| Computer | 200 | 20 | 10 |

What is the basic concept behind greedy algorithm?

The thief would choose the best item first, then the next best, and continue until he reached his limit. Of course, before doing this, the thief would have to decide what “best” should mean. Is the best item the most valuable, the least heavy, or maybe the item with the highest value-to-weight ratio?

Don’t under look a greedy algorithm. It is an algorithm:

- It sets the ruler to compare: the best.

- It shows the order of actions: one by one.

- It puts clear boundary: carry weight.

What is the implementation of three “best” greedy algorithm?

class Item (object):

"""

Class of loot item, including three attributes: <name, value, and weight>.

"""

def __init__(self, n, v, w):

"""

Init a instance of Item with name, value and weight.

:param n: string, name of item

:param v: float, value of item

:param w: float, value of item

"""

self.name = n

self.value = v

self.weight = w

def getName (self):

return self.name

def getValue (self):

return self.value

def getWeight (self):

return self.weight

def __str__(self):

result = '<' + self.name + ', ' + str (self.value)\

+ ', ' + str (self.weight) + '>'

return result

def value (item):

"""

Map "item" into its value.

:param item: an Item type item

:return: this item's value

"""

return item.getValue ()

def weightInverse (item):

"""

Map "item" into its weight's inverse value.

:param item: an Item type item

:return: this item's 1/weight

"""

return 1.0/item.getWeight ()

def density (item):

"""

Map "item" into its density(value/weight).

:param item: an Item type item

:return: this item's value/weight

"""

return item.getValue ()/item.getWeight ()

def greedy (items, maxWeight, keyFunction):

"""

Greedy is the core process of greedy algorithm. According to the keyFunction,

it puts the best items into knapsack until it is full.

:param items: list, of instances of Item.

:param maxWeight: float >= 0, the maximum weight a knapsack can contain.

:param keyFunction: function,

maps an item in a list to an comparable value accordingly,

as the second parameter of the `sorted` function

:return: a list of taken items, and a float of their total value

"""

# Use "what is my best" as the key function to sort a copied list of the items.

# Note the `sorted`'s algorithm efficiency is in O(n * log(n)).

itemsCopy = sorted (items, key = keyFunction, reverse = True)

result = []

totalValue, totalWeight = 0.0, 0.0

# Try each item in the sorted items list descendingly.

for i in range (len (itemsCopy)):

# Check whether the next biggest one could be taken into knapsack.

if (totalWeight + itemsCopy[i].getWeight ()) <= maxWeight:

result.append (itemsCopy[i])

# If new item is taken, update the total weight and value of result

totalWeight += itemsCopy[i].getWeight ()

totalValue += itemsCopy[i].getValue ()

return result, totalValue

def build_items ():

"""

Build a list of Items instances.

:return: a list of Items instances.

"""

names = ['clock','painting','radio','vase','book','computer']

values = [175,90,20,50,10,200]

weights = [10,9,4,2,1,20]

items = []

for i in range (len(values)):

items.append (Item(names[i], values[i], weights[i]))

return items

def test_greedy (items, maxWeight, keyFunction):

"""

Calculate for one sort of greedy strategy, and print its result.

:param items: a list of Items instances.

:param maxWeight: float, as the maximum weight a knapsack can hold.

:param keyFunction: function,

maps an item in a list to an comparable value accordingly,

as the second parameter of the `sorted` function

:return: None. Print out total value and items in taken loot.

"""

taken, val = greedy (items, maxWeight, keyFunction)

print ('Total value of items taken is', val)

for item in taken:

print (' ', item)

def test_diff_greedys (maxWeight = 20):

"""

Print out the results of different sorts of greedy strategy.

:param maxWeight: float, as the maximum weight a knapsack can hold,

with default value 20.0.

:return: None. Print out total value and items in taken loot of three sorts of strategy.

"""

items = build_items ()

# Greedy by value.

print ('Use greedy by value to fill knapsack of size', maxWeight)

test_greedy (items, maxWeight, value)

# Greedy by weight.

print ('\nUse greedy by weight to fill knapsack of size',

maxWeight)

test_greedy (items, maxWeight, weightInverse)

# Greedy by density.

print ('\nUse greedy by density to fill knapsack of size',

maxWeight)

test_greedy (items, maxWeight, density)Here we run it.

test_diff_greedys(maxWeight=20.0)## Use greedy by value to fill knapsack of size 20.0

## Total value of items taken is 200.0

## <computer, 200, 20>

##

## Use greedy by weight to fill knapsack of size 20.0

## Total value of items taken is 170.0

## <book, 10, 1>

## <vase, 50, 2>

## <radio, 20, 4>

## <painting, 90, 9>

##

## Use greedy by density to fill knapsack of size 20.0

## Total value of items taken is 255.0

## <vase, 50, 2>

## <clock, 175, 10>

## <book, 10, 1>

## <radio, 20, 4>How to formalize the 0/1 knapsack problem as an instance of a classic optimization problem?

The 0/1 knapsack problem can be formalized as follows:

- Each item is represented by a pair, <value, weight>.

- The knapsack can accommodate items with a total weight of no more than w.

- A vector, I, of length n, represents the set of available items. Each element of the vector is an item.

- A vector, V, of length n, is used to indicate whether or not each item is taken by the burglar. If V[i] = 1, item I[i] is taken. If V[i] = 0, item I[i] is not taken.

- Find a V that maximizes

\[ \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} V[i]^{*} I[i] . \text { value } \]

subject to the constraint that \[ \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} V[i] * I[i] . \text {weight} \leq w \]

How to implement the 0/1 knapsack problem’s formalization which is inherently exponential in the number of items in a straightforward way?

def get_binary_rep(positive_integer: int, num_bi_digits: int):

"""

Get int n's binary representation in a fix binary digits with leading zeros.

:param positive_integer: int, a non-negative decimal integer to be turned into binary number.

:param num_bi_digits: int, a non-negative decimal integer to set a fixed length of the

resulting binary number digits. It should be big enough.

:return: a string of '0's and '1's of length numDigits that is a binary representation

of n.

"""

binary_str = ''

while positive_integer > 0:

binary_str = str(positive_integer % 2) + binary_str

positive_integer = positive_integer // 2

if len(binary_str) > num_bi_digits:

raise ValueError('not enough digits')

for i in range(num_bi_digits- len(binary_str)):

binary_str = '0' + binary_str

return binary_str

def gen_power_set (ori_list): # O(2**len(ori_list)) * O(len (ori_list))

"""

Generate the power set of ori_list, including all subsets of the set of

ori_list's items.

E.g., if ori_list is [1, 2] it will return a list with elements

[], [1], [2], and [1,2].

Recall that every set is a subset of itself and the empty set is a subset of every set.

So the length of the power set is 2**len(ori_list).

:param ori_list: list

:return: a list of lists that contains all possible combinations of

the elements of ori_list.

"""

power_set = []

for i in range (0, 2**len(ori_list)): # O(2**len(ori_list))

bin_str = get_binary_rep(i, len(ori_list))

subset = []

for j in range(len(ori_list)): # O(len(ori_list))

if bin_str[j] == '1':

subset.append(ori_list[j])

power_set.append(subset)

return power_set

def choose_best(pset, max_weight, get_val, get_weight):

"""

Choose the best set of items from the power set of original list,

within the maximum weight budget of knapsack.

:param pset: list of lists, that contains all possible combinations of

the elements of ori_list.

:param max_weight: float or int, maximum weight budget of knapsack.

:param get_val: function or method, map an item in pset's list into its

comparable value

:param get_weight: function or method, map an item in pset's list into its

comparable weight

:return: a best set of items, and this best set's total value

"""

best_val = 0.0

best_set = None

for items in pset:

items_val = 0.0

items_weight = 0.0

for item in items:

items_val += get_val(item)

items_weight += get_weight(item)

if items_weight <= max_weight and items_val > best_val:

best_val = items_val

best_set = items

return best_set, best_val

def test_best(max_weight = 20):

"""

Run the choose_best function, and print its result in proper format.

:param max_weight: float or int, maximum weight budget of knapsack, default 20.

:return: None, print out the items taken and their total value.

"""

items = build_items()

pset = gen_power_set(items)

taken, val = choose_best(pset, max_weight, Item.getValue, Item.getWeight)

print('Total value of items taken is', val)

for item in taken:

print(item)Run test_best script.

test_best(max_weight=20)## Total value of items taken is 275.0

## <clock, 175, 10>

## <painting, 90, 9>

## <book, 10, 1>This result is different from the result of density.

Could this straightforward way be speeded up?

01.The gen_power_set could have had the header

def genPowerset(items, constraint, getVal, getWeight)and returned only those combinations that meet the weight constraint.Or

02.The choose_best could exit the inner loop as soon as the weight constraint is exceeded.

# def gen_power_set (ori_list): # O(2**len(ori_list)) * O(len (ori_list))

def gen_power_set_within_constraint(items, constraint, getWeight):

"""

Generate the power set of items which meet the weight constraint.

:param items: list, instances of Items.

:param constraint: float, maximum weight of knapsack.

:param getWeight: method, get weight of an Item.

:return: a list of lists that contains all possible combinations of

the elements that meet the weight constraint.

"""

power_set_within_constraint = []

for i in range (0, 2**len(items)): # O(2**len(ori_list))

bin_str = get_binary_rep(i, len(items))

subset = []

subset_total_weight = 0

for j in range(len(items)): # O(len(ori_list))

if bin_str[j] == '1':

subset.append(items[j])

subset_total_weight += items[j].getWeight()

if subset_total_weight <= constraint:

power_set_within_constraint.append(subset)

return power_set_within_constraint

# def choose_best(pset, max_weight, get_val, get_weight):

def choose_best_efficiently(pset, max_weight, get_val, get_weight):

"""

Choose the best set of items from the power set of original list,

within the maximum weight budget of knapsack.

:param pset: list of lists, that contains all possible combinations of

the elements of ori_list.

:param max_weight: float or int, maximum weight budget of knapsack.

:param get_val: function or method, map an item in pset's list into its

comparable value

:param get_weight: function or method, map an item in pset's list into its

comparable weight

:return: a best set of items, and this best set's total value

"""

best_val = 0.0

best_set = None

for items in pset:

items_val = 0.0

items_weight = 0.0

for item in items:

items_val += get_val(item)

items_weight += get_weight(item)

if items_weight > max_weight:

break

if items_weight <= max_weight and items_val > best_val:

best_val = items_val

best_set = items

return best_set, best_val

# def test_best(max_weight = 20):

def test_best_opt_01(max_weight = 20):

"""

Run the choose_best function, and print its result in proper format.

:param max_weight: float or int, maximum weight budget of knapsack, default 20.

:return: None, print out the items taken and their total value.

"""

items = build_items()

pset_within_constraint = gen_power_set_within_constraint(items, constraint=max_weight, getWeight=Item.getWeight)

taken, val = choose_best(pset_within_constraint, max_weight, Item.getValue, Item.getWeight)

print('Total value of items taken is', val)

for item in taken:

print(item)

# def test_best(max_weight = 20):

def test_best_opt_02(max_weight = 20):

"""

Run the choose_best function, and print its result in proper format.

:param max_weight: float or int, maximum weight budget of knapsack, default 20.

:return: None, print out the items taken and their total value.

"""

items = build_items()

pset = gen_power_set(items)

taken, val = choose_best_efficiently(pset, max_weight, Item.getValue, Item.getWeight)

print('Total value of items taken is', val)

for item in taken:

print(item)test_best_opt_01(max_weight=20)## Total value of items taken is 275.0

## <clock, 175, 10>

## <painting, 90, 9>

## <book, 10, 1>test_best_opt_02(max_weight=20)## Total value of items taken is 275.0

## <clock, 175, 10>

## <painting, 90, 9>

## <book, 10, 1>While these kinds of optimizations are often worth doing, they don’t address the fundamental issue. 【吴军老师写好算法后,工程主管要他做优化,省机器就是省钱,值工程师的时间。】

What is the essence of a greedy algorithm in compare with this power set algorithm?

The essence of a greedy algorithm is making the best (as defined by some metric) local choice at each step. It makes a choice that is locally optimal. However, as this example illustrates, a series of locally optimal decisions does not always lead to a solution that is globally optimal.

Why are greedy algorithms often used in practice, despite the fact that they do not always find the best solution?

They are usually easier to implement and more efficient to run than algorithms guaranteed to find optimal solutions. As Ivan Boesky once said, “I think greed is healthy. You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself.”

In what case, a greedy-by-density algorithm will always find the optimal solution?

There is a variant of the knapsack problem, called the fractional (or continuous) knapsack problem. Since the items are infinitely divisible, it always makes sense to take as much as possible of the item with the highest remaining value-to-weight ratio.

12.2 Graph Optimization Problems

What is the terms in the graph theory?

graph, node/vertex, edge/arc

A graph is a set of objects called nodes (or vertices) connected by a set of edges (or arcs).

digraph, source/parent, destination/child

If the edges are unidirectional the graph is called a directed graph or digraph. In a directed graph, if there is an edge from n1 to n2, we refer to n1 as the source or parent node and n2 as the destination or child node.

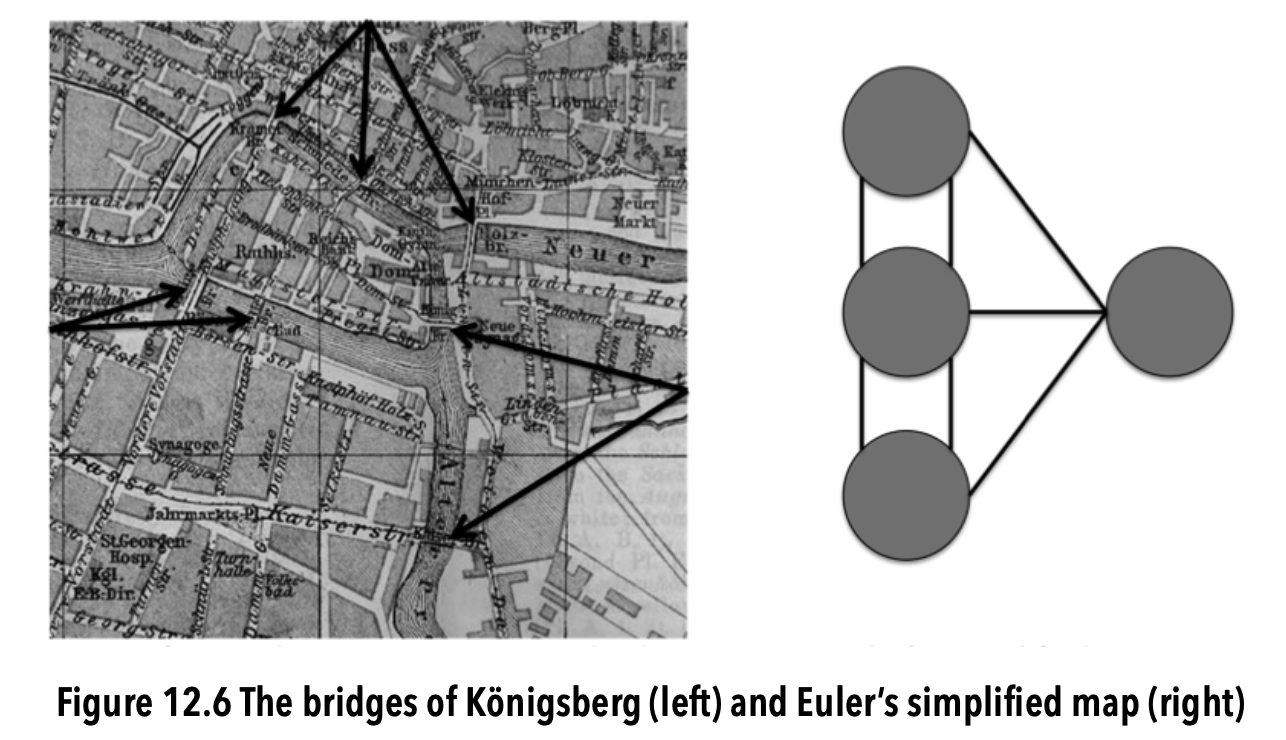

What is Euler’s insight into the problem of Königsberg bridges problem?

Euler’s great insight was that the problem could be vastly simplified by view- ing each separate landmass as a point (think “node”) and each bridge as a line (think “edge”) connecting two of these points. The map of the town could then be represented by the graph to the right of the map in Figure 12.6. Euler then reasoned that if a walk were to traverse each edge exactly once, it must be the case that each node in the middle of the walk (i.e., any island that is both entered and exited during the walk) must be connected by an even number of edges. Since none of the nodes in this graph has an even number of edges, Euler concluded that it is impossible to traverse each bridge exactly once.

image-20200619163859579

How to use graph theory to help understand problems? Give some examples.

Only one small extension to the kind of graph used by Euler is needed to model a country’s highway system. If a weight is associated with each edge in a graph (or digraph) it is called a weighted graph. Using weighted graphs, the highway system can be represented as a graph in which cities are represented by nodes and the highways connecting them as edges, where each edge is labeled with the distance between the two nodes. More generally, one can represent any road map (including those with one-way streets) by a weighted digraph.

Similarly, the structure of the World Wide Web can be represented as a digraph in which the nodes are Web pages and there is an edge from node 𝐴 to node 𝐵 if and only if there is a link to page 𝐵 on page 𝐴. Traffic patterns could be modeled by adding a weight to each edge indicating how often is it used.

There are also many less obvious uses of graphs. Biologists use graphs to model things ranging from the way proteins interact with each other to gene ex- pression networks. Physicists use graphs to describe phase transitions. Epidemi- ologists use graphs to model disease trajectories. And so on.

Why does it need to have a class for Node in implementing abstract types?

Implementation code of three classes

class Node (object):

def __init__(self, name):

"""

Initiate an instance of Node with its name.

:param name: str, identify a Node

"""

self.name = name

def get_name(self):

"""

Get a node's name string

:return: str, of a node's name.

"""

return self.name

def __str__(self):

"""

Give out the main information of a node to identify from other objects.

:return: str, of node's name.

"""

return self.name

class Edge (object):

def __init__(self, source, destination):

"""

Initiate an instance of edge with its source node and destination.

:param source: node, of an edge's source.

:param destination: node, of an edge's destination.

"""

self.source = source

self.destination = destination

def get_source(self):

"""

Get the source node of an edge.

:return: node, of an edge's source.

"""

return self.source

def get_destination(self):

"""

Get the destination node of an edge.

:return: node, of an edge's destination.

"""

return self.destination

def __str__(self):

"""

Represent a edge with its source and destination nodes.

:return: str, a representation of a unidirectional edge.

"""

return self.source.get_name () + '->' + self.destination.get_name ()

class WeightedEdge (Edge):

def __init__(self, source, destination, weight = 1.0):

"""

Initiate an instance of an weighted edge.

:param source: node, of an edge's source.

:param destination: node, of an edge's destination.

:param weight: float, a weight factor on an edge.

"""

self.source = source

self.destination = destination

#上面这两句也可以写成:

# Edge.__init__(self, source, dectination)

self.weight = weight

def get_weight(self):

"""

Get the weight of an weighted edge.

:return: float, the weight factor of an edge.

"""

return self.weight

def __str__(self):

"""

Represent a weighted edge with its source and destination nodes and weight value on the edge.

:return: str, a representation of a unidirectional edge with weight on its edge.

"""

return self.source.get_name () + '->(' + str (self.weight) + ')'\

+ self.destination.get_name()Barren superclass for subclasses of addition properties

Having a class for nodes may seem like overkill6. After all, none of the methods in class Node perform any interesting computation. We introduced the class merely to give us the flexibility of deciding, perhaps at some later point, to introduce a subclass of Node with additional properties.

What is the implementation code of Digraph and Graph classes?

class Digraph(object):

"""

Directional graph, with nodes as a list of nodes, and

edges as a dictionary of {parent:[children]} pairs,

i.e., a dict mapping each node to a list of its children.

"""

def __init__(self):

"""

Initiate an instance of digraph with its nodes as empty list,

and its edges as empty dictionary.

"""

self.nodes = []

self.edges = {}

def add_node(self, node):

"""

Add a node to its nodes list if it doesn't exist,

and add it to its edges as a new key.

:param node: a Node, as part of an Edge.

:return: none, alternating self.nodes and self.edges.

"""

if node in self.nodes:

raise ValueError ('Duplicate node')

else:

self.nodes.append(node)

self.edges[node] = [] # assuming all node could be a source of edge

def add_edge (self, edge):

"""

Add an edge to the digraph's edges dictionary,

under the condition that the edge's source and destination nodes

are already in the digraph's nodes list.

:param edge: an edge with source and destination nodes.

:return: none, alternating the self.edges dict.

"""

source = edge.get_source ()

destination = edge.get_destination ()

if not (source in self.nodes and destination in self.nodes):

raise ValueError ('Node not in graph')

self.edges[source].append(destination)

def children_of_node(self, node):

"""

Get the children nodes of a parent node.

:param node: a Node, as the parent node.

:return: list, of the children nodes.

"""

return self.edges[node]

def has_node (self, node):

"""

Check whether the digraph has this node.

:param node: a node object

:return: bool, true if node exists in digraph's nodes list.

"""

return node in self.nodes

def __str__(self):

"""

Represent a digraph with its source -> destinations relationship.

:return: str.

"""

result = ''

for source in self.nodes:

for destination in self.edges [source]:

result = result + source.get_name () + '->'\

+ destination.get_name () + '\n'

return result [:-1]

class Graph (Digraph):

"""

Graph class with no directional relation between two nodes.

"""

def add_edge (self, edge):

"""

Add edge with no direction between two nodes, i.e.,

adding a directional edge and its reverse one to Digraph.edges.

:param edge: an Edge with source and destination nodes.

:return: none, alternating the self.edges dict.

"""

Digraph.add_edge(self, edge)

# Duplicate an edge with reverse direction from destination to source.

rev_edge = Edge(edge.get_destination(), edge.get_source())

Digraph.add_edge(self, rev_edge)How to represent the Digraph in computer? What is the choice of its data structure?

One important decision is the choice of data structure used to represent a Digraph. One common representation is an n × n adjacency matrix, where n is the number of nodes in the graph. Each cell of the matrix contains information (e.g., weights) about the edges connecting the pair of nodes <𝑖, 𝑗>. If the edges are unweighted, each entry is True if and only if there is an edge from 𝑖 to 𝑗.

Another common representation is an adjacency list, which we use here. Class Digraph has two instance variables. The variable nodes is a Python list containing the names of the nodes in the Digraph. The connectivity of the nodes is represented using an adjacency list implemented as a dictionary. The variable edges is a dictionary that maps each Node in the Digraph to a list of the children of that Node.

Is it arbitrary that the choice of which one of Digraph and Graph to make the superclass?

There is an important substitution principle: If client code works correctly using an instance of the supertype, it should also work correctly when an instance of the subtype is substituted for the instance of the supertype.

There are many algorithms that work on graphs (by exploiting the symmetry of edges) that do not work on directed graphs.

What are the best-known graph optimization problems?

One of the nice things about formulating a problem using graph theory is that there are well-known algorithms for solving many optimization problems on graphs.

Shortest path

For some pair of nodes, 𝑛1 and 𝑛2, find the shortest sequence of edges <𝑠h, 𝑑h> (source node and destination node), such that

- The source node in the first edge is 𝑛1

- The destination node of the last edge is 𝑛2

- For all edges 𝑒1 and 𝑒2 in the sequence, if 𝑒2 follows 𝑒1 in the sequence, the source node of 𝑒2 is the destination node of 𝑒1.

Shortest weighted path

This is like the shortest path, except instead of choosing the shortest sequence of edges that connects two nodes, we define some function on the weights of the edges in the sequence (e.g., their sum) and minimize that value. This is the kind of problem solved by Google Maps when asked to compute driving directions between two points.

Maximum clique

A clique7 is a set of nodes such that there is an edge between each pair of nodes in the set. A maximum clique is a clique of the largest size in a graph.

Min cut

Given two sets of nodes in a graph, a cut is a set of edges whose removal eliminates all paths from each node in one set to each node in the other. The minimum cut is the smallest set of edges whose removal accomplishes this.

Where does the hypothetic “Six Degrees of Separation” come from?

In 1990 the playwright John Guare wrote Six Degrees of Separation. The dubious8 premise9 underlying the play is that “everybody on this planet is separated by only six other people.” By this he meant that if one built a social network including every person on the earth using the relation “knows,” the shortest path between any two individuals would pass through at most six other nodes.

A less hypothetical10 question is the distance using the “friend” relation between pairs of people on Facebook.

How to print a path?

def print_path(path):

"""

Construct a string representing a path.

:param path: list, of nodes.

:return: string.

"""

result_str = ''

for i in range(len(path)): # use index, not element.

result_str = result_str + str(path[i])

# result += str(node) # for node in path:

if i!= len(path) - 1:

result_str = result_str + '->'

return result_strHow to do a deep first search?

airfare: the price to be paid by an aircraft passenger for a particular journey: save a bundle in airfare by flying standby.↩

honor_v.t.: make sure the franchisees honour the terms of the contract: fulfil, observe, keep, discharge, implement, perform, execute, effect, obey, heed, follow, carry out, carry through, keep to, abide by, adhere to, comply with, conform to, act in accordance with, be true to, be faithful to, live up to; rare effectuate. ANTONYMS disobey.↩

Syn. – Limit; bound; border; term; termination; barrier; verge; confines; precinct. Bound, Boundary. Boundary, in its original and strictest sense, is a visible object or mark indicating a limit. Bound is the limit itself. But in ordinary usage the two words are made interchangeable.↩

knapsack: noun RUCKSACK, BACKPACK, haversack, pack, kitbag, duffel bag, satchel, shoulder bag; British holdall.↩

loot: Plunder; booty; especially, the booty taken in a conquered or sacked city.↩

overkill: n [U] (usually fig) much greater amount than is needed to defeat sb/sth or achieve sth. It was surely overkill to screen three interviews on the same subject in one evening.↩

clique: A narrow circle of persons associated by common interests or for the accomplishment of a common purpose; – generally used in a bad sense.↩

dubious: Occasioning doubt; not clear, or obvious; equivocal; questionable; doubtful; as, a dubious answer.Wiping the dingy shirt with a still more dubious pocket handkerchief. - Thackeray. Syn. – Doubtful; doubting; unsettled; undetermined; equivocal; uncertain. Cf. Doubtful.↩

premise: A proposition antecedently supposed or proved; something previously stated or assumed as the basis of further argument; a condition; a supposition. The premises observed,Thy will by my performance shall be served. - Shak.↩

hypothetical: Characterized by, or of the nature of, an hypothesis; conditional; assumed without proof, for the purpose of reasoning and deducing proof, or of accounting for some fact or phenomenon.↩